Story of the Book

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

In the first half of the Twentieth Century, the First and Second World Wars together lasted ten years and 80 million people were killed. There were only twenty-one years between these wars and no nuclear weapons in existence. The First World War had been dubbed, 'war to end all wars'. So why did mankind rush so quickly into a Second World War? The answer is that In those days, warmongers such as Hitler, expected to win.

The Cold War (1945-1990), lasted forty-five years with both the Soviet Union and the Western Allies (NATO) having the power to destroy each other. Both sides understood that. 'There could be no winner in a third world war,' said Nikita Kruschev, the Soviet leader. Terrifying though the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction was, it is what underpinned the 75 years of peace Britain has enjoyed since the end of the Second World War. History has shown that nuclear deterrence works.. The Cold War ended peacefully.

My career in the Navy spanned thirty-seven years (1961-98), most of it during the Cold War and much of it involved in our strategic nuclear deterrent programme. By preventing a third world war, the thousands engaged in this peacekeeping mission were providing the greatest public service of all: PEACE. But it was all so secret. The general public have known virtually nothing about it and many have been misinformed. I felt the need to plug that information gap. I wanted to leave a public record of what life was like for those who served in our submarines during the Cold War.

WHY I FELT THE NEED TO WRITE THE BOOK

As I was born during the Second World War, I was weaned on stories of heroism, patriotism, hardship and death. The new dimension was that my generation faced the prospect of nuclear obliteration. We grew up in the knowledge that we would have only four minutes notice of incoming Soviet missiles and nuclear armageddon. The Fylingdales radar station in Yorkshire was built to provide that warning. Hitler's Fascist threat in the Second World War had simply been replaced by Communism, another enemy that sought world domination.

Nuclear submarines and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) were invented when I was at school and, conscious that Hitler's U-boats had almost starved Britain into defeat, I recognised that nuclear-powered submarines were best equipped to hunt and kill enemy submarines. However, the Americans were also developing another type of nuclear-powered submarine, one which could launch Intercontinental ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads from unknown locations beneath the sea. This created an invulnerable nuclear counter-attack capability, continulousy ready at fifteen minutes notice to launch a nuclear counter strike.

This was the submarine-launched strategic nuclear deterrent, utterly warlike but a force for peace. These submarines, SSBNs in the jargon, would not enter Royal Navy service until 1968, the year I volunteered for submarines. Until then, RAF V-bombers would carry Britain's nuclear deterrent. I joined the Royal Navy in 1961, only sixteen years after the end of the Second World War.

WRITING THE BOOK

Writing a book is hard, demanding work, which calls for determination, persistence and self-discipline. Never waste a moment. I have spent countless hours with my laptop in airports, trains and on holiday. 'On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service' took me about four years to complete.

It began life as 'Children of the Nuclear Age', my concept being that the Nuclear Age began the year I was born (1943) with the ultra top secret Manhattan Project, its work being revealed to the world only in 1945 when the first atomic bombs were dropped. I was fascinated by the idea that I had been one of the first children of the Nuclear Age and then had grown up to be fully engaged in Britain's Strategic Nuclear Deterrent. I was truly a child of my time. The book would describe life under my nuclear umbrella from childhood to retirement.

I entered early draft chapters for 'non published work' competitions and thus gathered some excellent critiques. I also ran draft chapters past fellow members of the Helensburgh Writers' Workshop, comprised mainly of middle to older aged females, and gained further feedback; the ladies liked it. One thing stood out however; the title failed to grab people. So, before offering the finished manuscript to an agent, I changed the title to 'On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service'. It was a spontaneous idea but it did the trick.

I hooked the agent I had targeted at the first attempt. Ian Drury of Sheil Land Associates, a top London literary agent, thought the title was brilliant but the book failed his Ronseal test; i.e. it did not do what it said on the tin. 'Someone picking up a title like that,' he said, 'does not expect the first 150 pages to be about a boy growing up in Coatbridge. If you get rid of your childhood and add in more about submarines, 120,000 words altogether, it could be publishable.' I had the wisdom to follow his advice. So, three years of work went into the bin and I had to add another nine chapters which had never been my intention. That worked.

PUBLISHING CONTRACT

Things were now moving. My agent sent me a publishing contract with Casemate UK for signing . All very exciting but a bit scarey; the contract held me personally responsible for any defamation of character or breach of copyright.

Sorting out copyright on old photos was the devil of a job; two of the photographic companies listed on photos I had carefully chosen were long since out of business but their copyright could have been sold on to other companies or passed in wills to family. All too difficult; I did not use such photos. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the US Navy came up trumps and allowed me to use all of their photographs. For this type of book, I had also to ensure that I was not breaching the Official Secrets Act. As I was well aware of what information should not be divulged, this was not a problem and MOD gave me security clearance virtually without challenge.

As this was an autobiography, real people were involved and I had to ensure that I was not guilty of libel. That was much more sensitive. This was not a kiss-and-tell story and I had absolutely no desire to settle old scores or stab former colleagues in the back but it was still necessary to describe difficult inter-personal experiences. So, where I felt that offence may be caused, I used fictitious names. As the book was about my personal character development, the few name changes did not diminish it. As far as I could, I tracked down all the people I had mentioned and sent them copies of the relevant manuscript pages, a time-consuming task and a white knuckle ride when writing to people with whom I had crossed swords.

This latter process could have raised real problems if too many of my subjects had demanded major changes or threatened legal action. In reality, few did and several offered extra tit bits for inclusion. It was in the end a life re-affirming experience. I found myself entering into the warmest of e-mail exchanges with old colleagues and former bosses. The most touching was a most generous reply from a former Captain who had sacked me in my first job; he had been a bete noir for about thirty years.

WARNING: Putative memoir writers beware: one former senior officer with whom I had crossed swords, despite his name not being given in the book, took serious exception to my description of our clash. Out of courtesy, I had sent him a draft for comment. He was hostile, hinted at legal action and subsequently wrote a character assassination of me disguised as a book review in the Naval Review. That action entirely vindicated my description of him and gained me unsolicited support from other readers of the Naval Review through letters to the editor. Two other former colleagues who were named fictitiously in the book, recognised themselves and gave adverse feedback comments on Amazon; I could recognise who they were. I have now received over fifty five-star ratings on Amazon at the last count.

MEETING MY PUBLISHER

The moment I had dreamt of: on 30th June, 2017, I met my publisher for the first time. Casemate (UK) is based in Oxford and specialises in military history. I met Clare Litt, the Publishing Director, and Tom Bonnington, the Marketing Executive, in the Ashmolean Museum - clearly I was viewed as an old fossil! We hit it off straight away.

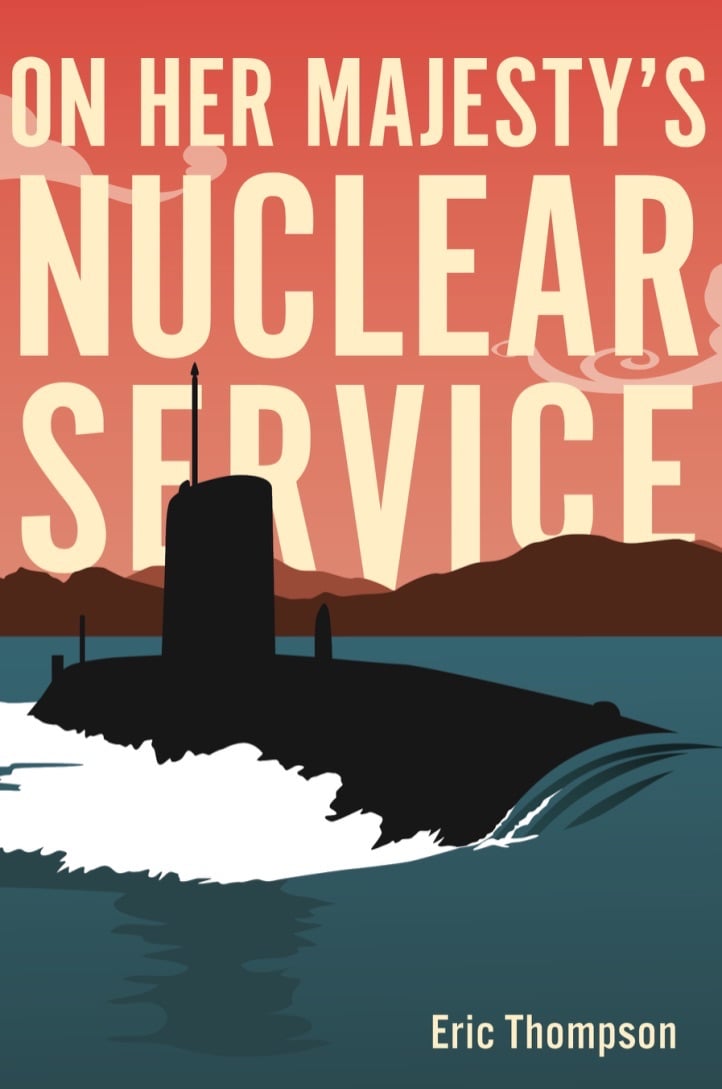

On first contacting me, Casemate had asked for any suggestions I had for a cover and I sent them a photograph. Now Clare ambushed me with their graphic artist's cover design and asked for my opinion. I thought it was brilliant. It is a really dynamic cover, worthy of a thriller, and far better than a photograph. That's where the skill of a professional graphic designer comes in.

Getting the cover done is the first priority for a publisher. New books have to go into trade catalogues well ahead of actual publishing. My cover appeared in Casemate's Spring 2018 Catalogue. After that, professional editors/readers attack the manuscript and may call for changes. Mine did not. My manuscript had already been so well edited that virtually no changes were necessary. I was chuffed by that. Advance copies are then sent to book reviewers. After that, the print copy surfaces for final agreement; a sort of speak now or forever hold your peace moment. After years of slogging away on my laptop, it was difficult to believe that this was actually happening.

Then it's on to marketing.

MARKETING

Once a book is published, it has to be promoted, another task in its own right. Very large publishers may have a marketing department. Smaller publishers do not. Ultimately, the author has to do much of the marketing.

In my case, I had some previous experience of media management and my younger son was in that business. Thus, I did gain some excellent coverage in the Scottish media, including TV interviews, but was unable to penetrate the UK national broadsheets or TV channels. I did however get a full page spread in the Mail on Sunday. Casemate's US office also set me up for a one hour live radio interview on a US Radio book programme.

Book festivals seem to be difficult to break into because they want well-known authors to bring in the crowds and make the festival financially viable. From my point of view, the economic benefits of attending book festivals at long range, don't add up. I did manage to gain a place in Glasgow's Aye Write lierary festival and the Berwick-on-Tweed Literary Festival. Both were most enjoyable and I was received with great respect by full audiences (very humbling).

Casemate made me a once-only offer of a minimum of 200 books at wholesale price. I was given 24 hours to decide. Hmmm? Could I personally sell that many? i had to show confidence in my own book. I took a gamble and ordered 200. I have probably donated or given away more than half but that has been a pleasure. Publishers tend not to do book launches any more; it's not economic. So, I organised my own in the Scottish Submarine Centre with Casemate doing the sales.