BIOGRAPHY

COMMODORE FREDERIC GLADWYN THOMPSON

MBE MSc CEng FIEE RN DL

Known as 'Eric'

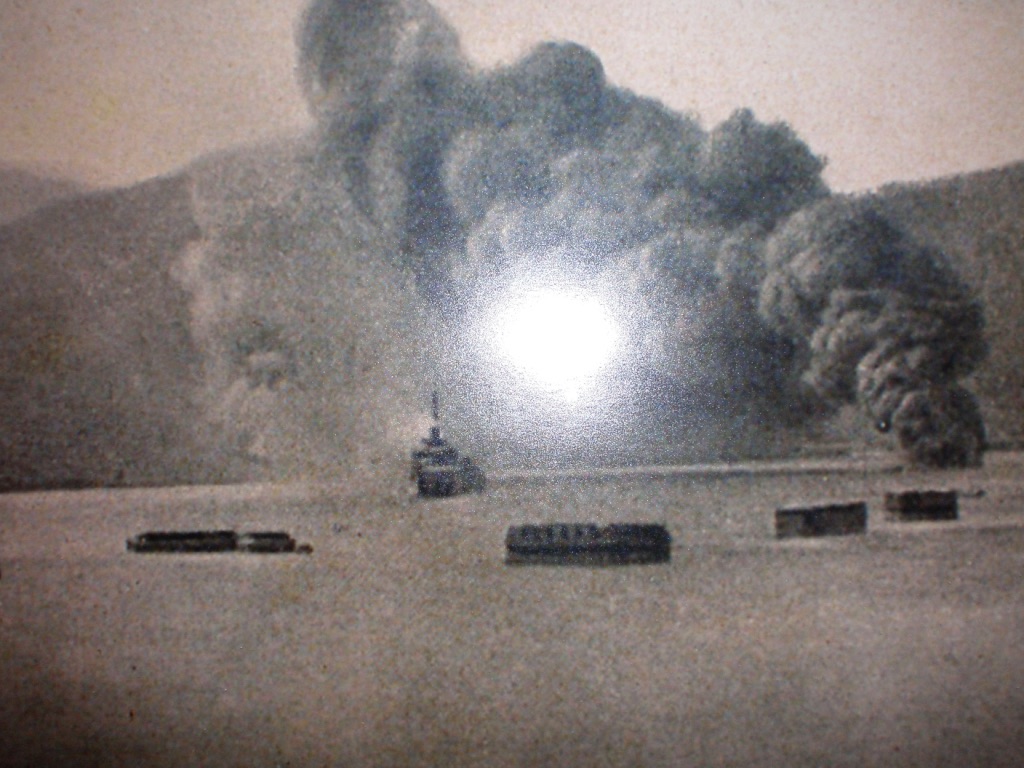

I was born in Coatbridge, Scotland, on 9th November, 1943, six weeks after my father's ship, HMS Intrepid, was sunk by German bombers at Leros in the Greek Dodecanese Islands. (see under 'Royal Navy'). (Leros was the fictional Navarone in Alistair Maclean's novel/film, 'The Guns of Navarone').

My father survived the sinking and turned up later but by then, I had been given his name. Thereafter, I became F G Thompson Junior, 'Junior' becoming my working title.

1943 was the year the Second World War turned in our favour. Victory was achieved when I was two but the impact of the War dominated my childhood thinking; I was weaned on heroism and sacrifice.

The Second World War ended with the first use of nuclear weapons and, whether one likes it or not, the world has lived ever since under a nuclear umbrella. These weapons have not disappeared. They have been the ultimate sanction against a third world war. Ironically, they have become a force for peace. Later generations may be less conscious of this but my generation grew up acutely aware that nuclear armageddon was a distinct possibility. We were living through the Cold War and knew that we would have only a four-minute warning of an incoming nuclear missile attack. Nothing has changed in this respect except time. The missiles still exist.

After 44 years, the Cold War ended peacefully and it is now 75 years since the end of the the Second World War. My generation and all succeeding British generations, have lived in peace.

Coatbridge 1943-1961

Coatbridge (pop. 52,000), once known as the Iron Burgh on account of the number of iron works, was the epitome of an industrial town. The Monklands canal carried its produce to the shipbuilding and heavy engineering industries in Glasgow. It was possibly the most unfashionable town in the British Empire. Even its football team, Albion Rovers, dared not mention its name but it was a great place to live during those immediate post-war years. The community spirit was second to none; education was an imperative; the upward mobility ladder was there for all to grasp. It offered the best of both worlds, easy access to the big city and equally easy access on foot or by bike to the open countryside.

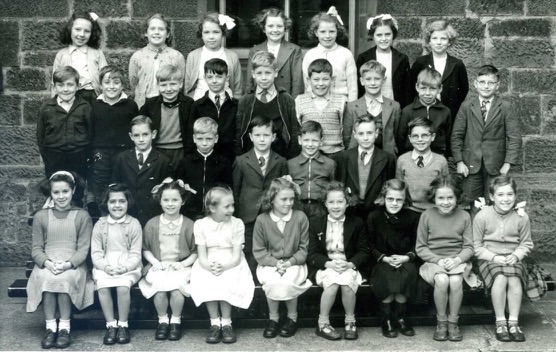

Coatdyke Primary School (now demolished) was an old-fashioned, no nonsense seat of learning. Apart from teaching the three Rs, its aim was to get the academically more able pupils through their Qualifying Exam (11+). Those who 'qualified' proceeded to the superb Coatbridge High School, where the aim was to get the most academically gifted onwards into University. I was fortunate to have been in the 'academically gifted' group but felt it wrong even then that so many of my primary school chums were sent to the junior secondary with a leaving age of fifteen. It would have been far better to have one secondary school for the town, the same uniform for all, including Catholics, but with academic streaming.

In both schools, corporal punishment (the tawse) was used regularly by both male and femal teachers. I experienced many painful 'beltings' - far better than being given a hundred lines to write. I had and still have no objections to use of the tawse but am not in favour of the English habit of caning on the backside, which seems to have sado-masochistic implications.

My aim at school was to qualify for officer entry into the Royal Navy. That demanded similar academic entry standards to universities plus a three day interview process. Coatbridge HIgh School did not let me down. At sixteen, I won a scholarship to Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. To this day, I still thank my wonderful teachers for the great start they gave me. At school, my main intersts were football, running, cycling, sailing, tennis, badminton, debating society, school opera, Citizens' theatre club, the excellent 2nd Coatbridge Scouts with its inspirational leaders, Cliftonville Community Association Youth Club created and managed by we teenagers with no adult involvement, camping, youth hosteling and, of course, the girls, some of whom I had known since primary school. What a childhood!

Alas, Coatbridge had one great social fault line. Due to the number of Catholic Irish labourers who came to the town during the Industrial Revolution, 60% of the town's population was of Irish Catholic descent. It was like a transplant from Belfast. We lived in parallel worlds. Although I grew up in the Protestant community, I was entirely ecumenical in spirit but mixing with the Catholics was virtually impossible. We went to separate churches, separate schools and even separate Scout groups. As secretary of the school debating society, I broke this sectarian mould by inviting St Patrick's High School to visit us for a joint debate but on the football field, it was a different story. Playing against St Patrick's was like a juvenile Rangers v Celtic match.

Coatbridge High School was then one of the top footballing schools in Scotland. We reached the final of the Scottish Schools Senior Shield competition in both my fifth and sixth years, the finals being played at Hampden, the national stadium. Tragedy upon tragedy, in both finals we were beaten by Catholic schools (St Mungo's Academy of Glasgow and Our Lady's High School of Motherwell). The reason for these defeats was obvious; our opponents had brought busloads of priests to support them!

Ironically, my first friends in the Navy happened to be Catholic. I discovered this only when they fell-out from Sunday divisions to attend the Catholic church service. 'I didn't know Catholics were like you,' said I to Tony. 'What do you mean?' he asked. That brought home to me, the nonsense of having religious apartheid in our schooling.

Coatbridge gave me the firmest of foundations for life, a fantastic childhood and a moral compass.

NAVAL CAREER 1961-98

At age seventeen, I entered Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, a life-changing transition. In my final year at school, I had read John Winton's hilarious novel, 'We Joined the Navy', about young officer cadets at Dartmouth. It was my only source of information on what I was about to receive. The book had taught me to look for the humorous side of life in the Navy: 'If you can't take a joke, you shouldn't have joined.' Much Later, I discovered that the author had been a submarine engineer officer, which I was destined to be. My freedom had gone and it was men only but I loved it. At Dartmouth, I was remoulded into a Naval Officer. It was a tough regime, especially at sea in the Training Squadron.

Dartmouth then was emerging from having been an exclusive, English-style, public school. It was here that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth was introduced to Prince Philip of Greece, a student, through an introduction engineered by his uncle, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Louis Mountbatten. Alas, the good Lord failed to fix me up with Princess Margaret. The College was now accepting 'grammar school' boys if academically able and fit in all other respects for officer training. Of course, with my Scottish accent, I immediately became known as Jock.

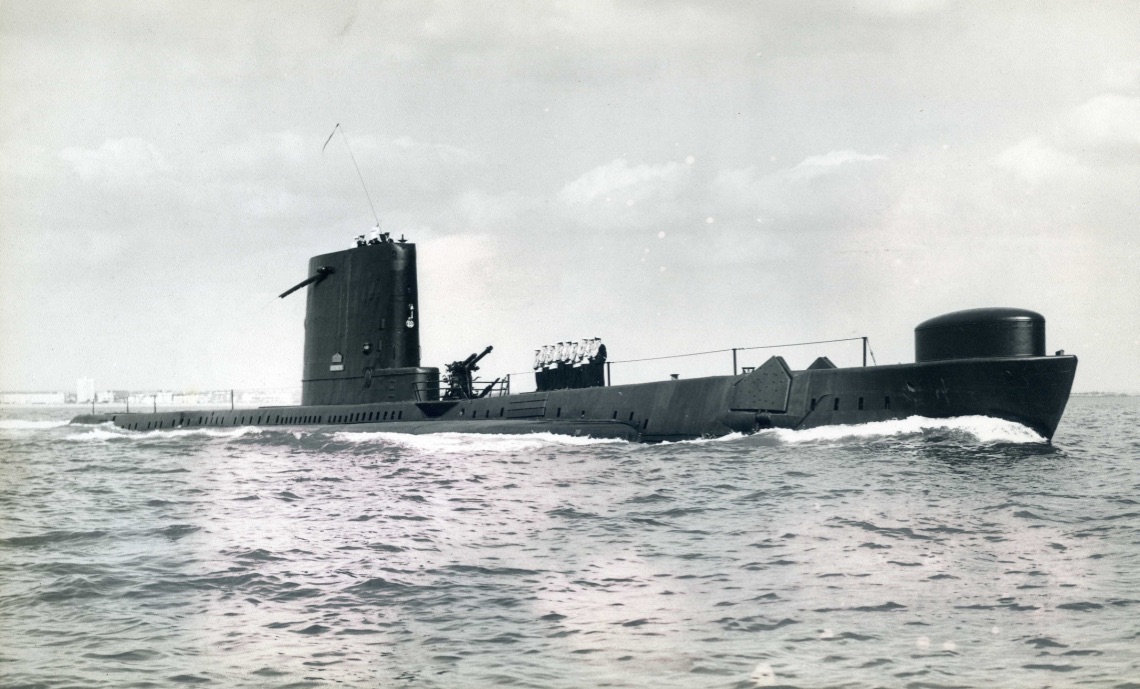

As a creature of the Cold War, I would serve in HM Ships Vigilant, Hermes, and Barrosa and HM Submarines Andrew, Otter, Osiris, Conqueror and Revenge.

After a year in the destroyer, HMS Barrosa, in the Far East Fleet, based in Singapore, I gained my Commission and proceeded to the Royal Naval Engineering College, Manadon to read Electrical Engineering.

I had joined the Royal Navy with the intention of becoming a destroyer captain or a fast jet pilot but was too short-sighted to be either. So, I opted to become an Engineer and volunteered for submarines where eyesight was required only for watching dials and movies. Not true; in submarines I kept both bridge and persicope watches.

Manadon (aka the Plymouth monosex monotech) must have been the most exclusive college in the world. Its students were men only, all commissioned officers on full pay, all committed to a Naval career for life, and there was only one faculty, Engineering, in its various manifestations. Simultaneously, we were treated both as schoolboys and young gentlemen. It was not in any way comparable to a university. I regretted that.

The compensation was the fellowship of my brother Engineers. We were the men who would keep the seagoing Navy operational, manage huge technical projects such as the building or refitting of nuclear-powered submarines and aircraft carriers etc. What's more, we would be colleagues in these endeavours for the rest of our careers, particularly so for the submariners. Britain's burgeoning flotilla of nuclear-powered submarines required at least six graduate engineers per boat. Submarine Engineers were a club within a club within a club. I feel intensely proud to have been a member

STARTING A FAMILY

Whilst at Manadon, I met and married Catriona Thomson (Kate) from Uddingston, only five miles from Coatbridge. We met on the train, in Perth Station to be exact. We were both going on a ski-ing course at Glenmore Lodge, an outward bound school near Aviemore in the Cairngorms. We would remain happily married till Death did us part forty years later.

Before leaving Manadon, our first son, Richard, was born. By then, we had Parahandy, our first Alsatian, as both pet and guardian for Kate and Richard and later Andrew, when I was at sea. Submarine training followed and then I was appointed in succession to three diesel submarines, HMS Andrew, Otter and Osiris.

The full story of my career in submarines is in 'On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service'.

Following sea time in submarines, I concentrated on improving our underwater warfare capability, spending five years developing the Tigerfish torpedo. Soviet nuclear submarines were now a huge threat to national security. We had to be able to defeat them.

Nuclear Training

1974 - On being selected for nuclear propulsion (as opposed to nuclear weapon) training, I studied for a post graduate diploma in Nuclear Reactor Technology at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. This was living history, ancient and modern. We dined in the famous Painted Hall but in the basement was a small nuclear reactor. Utterly bizarre.

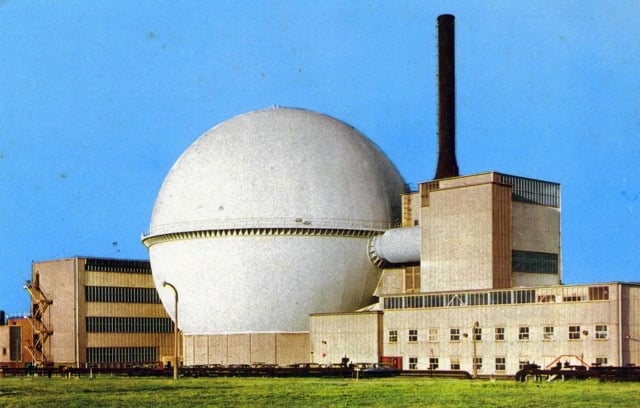

After theoretical nuclear training at Greenwich, the class decamped to the very North of Scotland, to the UK Atomic Energy Authority site at Dounreay, easily recognised by its massive containment sphere. What is less well known is that the Navy had a protoype submarine nuclear propulsion plant there for research and development purposes. This was where our practical training was carried out.

On completion, I joined HMS Conqueror, thence HMS Revenge. Revenge was one of our four strategic nuclear deterrent submarines. Her role was to prevent a third world war, a role I was proud to play. Her task was simply to disappear for months on end, remaining at all times ready to obey a firing signal from the Prime Minister, a political, not military, decision.

During my last patrol in Revenge, we suffered a major steam leak. I happened to be on watch. My moment of truth had come. We were at risk of being poached alive. We could have evacuated the engine rooms but that would have forced the submarine to surface in her top secret patrol position and signal for a tug, a massive national embarrassment. Fortunately, my team saved the day but for the next nine weeks we had to survive in a crippled state. No one knew. We were on our own. Submarines on deterrent patrol do not send signals. As a result, I was awarded an MBE for technical leadership. LMEM 'Bungy' McWilliams was awarded a Queen's Gallantry Medal and five of the team were awarded Oak Leaves for gallant conduct (i.e. Mentioned in Despatches). After years of worrying about whether or not I was good enough, I had proved it when the chips were down.

After nuclear sea time, I specialised once more in underwater warfare. This included sonar, homing torpedoes and stealth technology. It was the cutting edge of Cold War submarine technology. As underwater warfare is all about sound, I took a Masters degree in Acoustics at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh (at my own expense). After various staff appointments in Submarine HQ, Squadrons, and the Ministry of Defence, I finally emerged as Chief Engineer and ultimately Commodore-in-charge (i.e. Managing Director) of HM Naval Base Clyde at Faslane, the home of the UK's strategic nuclear deterrent.

POST NAVAL LIFE

On retiring from the Navy, I decided to become involved in politics and stood as the Liberal Democrat candidate for the Dumbarton constituency in both Scottish and Westminster parliamentary elections. It was then a very safe Labour seat but I gained 4,500 votes, one of the largest Lib Dem votes in Scotland, only a few hundred behind the Scottish Nationalists and ahead of the Conservatives. I was, however, successsfully elected (twice) as Councillor for Helensbrugh East in Argyll & Bute Council. Serving the public came naturally to me after thirty-seven years of serving the country but I struggled to empathise with political groupings and self-interest, a very different culture from the Navy. After eight honourable years, I stood down from politics.

I also served on Strathclyde Police Board, the Lomond and Argyll Primary Care NHS Trust and, almost as a self-test, worked as a freelance management consultant. I had the honour of being appointed by Her Majesty the Queen as a Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Dunbartonshire, am a Freeman of the City of Glasgow and Past President of the illustrious Bridgeton Burns Club. My private interest, however, has been to write in various forms; comic verse, after-dinner speeches, a humorous novel (still unpublished) and 'On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service', my personal homage to the Submarine Service.

As a writer, I have won several literary prizes, in particular the Scottish Association of Writers Constable Trophy for best (unpublished) novel. 'On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service' was runner-up in a shortlist of 38 entries in the Mountbatten Best Book Award 2018 and has been an astonishing success in so many ways. Not only because of international recognition, excellent reviews in the media, a highly favourable interview on an American radio book review programme (see link in OHMNS section) and three reprints in its first six months but also because I have received so many highly favourable comments from former colleagues and complete strangers, all gratefully received and hugely life enriching. Currently OHMNS has over 50 5-star reviews on Amazon and this year (2020) comes out as a paper back, a mark of publishing success.

I have always sought to bring humour to the party and have published three books of humorous verse: Colquhounsville-sur-Mer, Democracy for Birds and Love Songs for the Romantically Challenged.

When I say that I have been blessed, it's almost true but in 2005, after 40 years of being totally committed to each other, tragedy struck. I lost my beloved Kate to breast cancer. It was an Indescribably devasting loss. It is to Kate that I have dedicated On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service. Without her rock steady support, I doubt if I could have survived thirty-seven years in the Navy.

Life had to begin again.