Media Coverage

The Sunday Herald Faslane: 50 years of nukes on the Clyde

22ND MAY, 2018

Jody Harrison

Reporter

FOR half a century it has been home to Britain’s nuclear deterrent – missiles capable of mass destruction borne on powerful vessels which travel silently around the globe.

HM Naval Base Clyde, commonly known as Faslane, is a site that has provoked impassioned debate. Some say its arsenal has helped preserve peace since the end of the Second World War, while others – not least the Scottish Government – have condemned it as a costly and reckless mistake which inches the world closer to doomsday.

Today it is Scotland’s largest military base – providing jobs for almost 7,000 people and massively contributing to the economy of Argyll. Yet its business costs millions to maintain, and will cost billions to replace in the future, with many arguing the money would be better spent on schools and hospitals.

The base, then called HMS Neptune, was officially opened in 1968 by the Queen Mother as a home for the submarines of the Polaris weapons system, the predecessor to the Trident nuclear deterrent. Later that year, HMS Resolution conducted the first operational Polaris patrol and in 1969 the UK fully adopted its policy of Continuous At Sea Deterrence, which remains unbroken to this day. This sees at least one submarine always on patrol somewhere in the world, ready to strike back if the UK comes under nuclear attack. It is a policy of mutually assured destruction. Should an enemy nation fire on Britain, it does so in the knowledge it ensures its own obliteration. Unseen and undetectable, Faslane’s nuclear submarines would launch their own payloads even if Britain is overwhelmed, replying kind for kind.

Eric Thompson, the former Commodore at Faslane, believes the base and its complement of submarines has kept the world safe. He said: “I volunteered for submarines in 1968 at the height of the Cold War. The Red Army had invaded Hungary and was about to invade Czechoslovakia. The Vietnam War was raging. “Little did I know that 30 years later, I would be Commodore in charge of the Base, the Cold War would have ended peacefully and that 50 years later our deterrent submarines would still be continuously patrolling. Nowadays, people in Britain take peace for granted, few sparing the slightest thought for our submariners out there on patrol. Lest we forget, in the first half of the 20th Century, there were two horrific world wars involving both mass destruction and megadeath, with 80 million killed. That was before nuclear weapons were invented. It is now 73 years since the end of the Second World War and three generations of British citizens have never known war. That is not by accident. It is because of our (NATO) nuclear deterrent force. Over the past 50 years, hundreds of thousands of Scots have benefited economically from Faslane but we must never forget that its purpose is to maintain our peace.”

The UK transitioned from Polaris to the Trident missile system and HMS Vanguard carried out the first operational Trident patrol in December 1994. From 2020 the base will become the sole home of the UK Submarine Service as well as the future home of the Dreadnought class of nuclear deterrent submarines, with the workforce expected to increase to 8,500. Yet for all the might within, outside the massive base’s gates can be found its direct counterpoint. Just along the road a collection of colourful, ramshackle huts, caravans and trailers mark the site of the Faslane Peace Camp, the longest-occupied peace camp in the world. For 35 years, an ever-shifting cast of activists, drop-outs and dreamers have called the camp their home, organising regular protests and defiance against the nuclear arsenal. Many of these acts can result in a criminal conviction, yet the peace campers continue on undeterred as the years roll by.

Kate Hudson, general secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) thinks the opposition would continue as long as the base is open. She said: “Fifty years of nuclear weapons subs at Faslane has meant 50 years of protest against these weapons of death and destruction. Across the decades, Faslane has been a key focus for the anti-nuclear movement, with blockades, the peace camp, direct action, protests and vigils – with national and international participation. It has come to symbolise both the terror that is nuclear weapons and the courageous democratic struggle that is opposition to these weapons of mass destruction.”

Ms Hudson added: “Our view – and that of the majority of Scottish parliamentarians and people – is that the UK should back the UN’s new treaty to ban all nuclear weapons globally. It’s time for the UK to join the global majority and end its nuclear role. Time for the denuclearisation of Faslane.”

The National

Former Faslane chief says Trident crews are 'the real peacekeepers'

Martin Hannan

Journalist

Former Clyde base commander Eric Thompson claims CND and the Faslane Peace Camp have done ‘absolutely nothing to safeguard peace'.

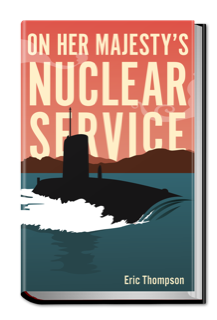

A former commander of the Clyde Submarine Base has launched an astonishing attack on peace campaigners such as CND and the Faslane Peace Camp. In an article to plug his book, entitled On Her Majesty’s Nuclear Service, Commodore Eric Thompson says that Trident submariners are the true peacekeepers, while “pacifists and anti-nuclear protesters have done absolutely nothing to safeguard our peace”.

In an article for Forces.net, Coatbridge-born Thompson, who has stood for the Lib Dems in both Holyrood and Westminster elections, wrote: “One of the unseen crosses servicemen and women have to bear is that of not being able to defend their role in public. That is the job of politicians and, on their behalves, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) press office. The MoD, however, tends to issue bland, defensive and non-controversial press releases, eg: ‘The Ministry can neither confirm nor deny’. Rule 1 being that the Minister must never be embarrassed. As a submarine officer, I found it galling to drive past a so-called Peace Camp at the gates of Faslane and having to suffer (along with other law-abiding citizens) from the traffic jams caused by CND ‘Peace’ demonstrations forming roadblocks, the latter being attended by left-wing politicians hoping to create a photo opportunity of themselves being arrested at the main gates of the base.”

Thompson continues: “The facts are quite simple. In the first half of the 20th century, there were the two most horrific wars in the history of the human race and that was before nuclear weapons were invented. The First World War was dubbed ‘the war to end all wars’, yet a mere 21 years later, we had the even greater horror of the Second World War in which 60 million people were slaughtered. World War 2 was terminated by the first use of nuclear weapons, not begun by them.”

Thompson claims the mutually assured destruction philosophy has been proven. He says: “The success of this policy has indisputably been proved twice. First, in the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 when the Soviets had secretly smuggled intermediate-range nuclear missiles into Fidel Castro’s communist Cuba, missiles capable of targeting the whole of the USA. President Kennedy had an election to face and had to be seen to act tough; President Kruschev had the prestige of international communism at stake and could not be seen to back down. In the end, Kruschev backed down, claiming correctly that ‘human reason had won’. There would have been no winners in a nuclear world war.

“The second clear proof is that, after 46 years, the Cold War never did degenerate into a third world war. I would argue that a third proof in today’s world is President Putin of Russia did not simply invade Ukraine to reclaim the Crimea. He could have done so easily but did not want to risk things escalating out of control into a third world war. So, he reclaimed the Crimea by stealth and subversion."

Thompson concludes: “The bottom line is clear. Pacifists and anti-nuclear protesters have done absolutely nothing to safeguard our peace. It is the submariners on continuous at sea deterrent patrol who are the true peacekeepers.”

Ellen Renton, convenor of Helensburgh CND which is the nearest branch to Faslane, said she was shocked at the former commodore’s claims that his submariners were the “true peacekeepers”. She said: “Nine crew were kicked out of the Navy last October for having hard drugs and committing other offences aboard HMS Vigilant, on which he [Thompson] was an officer. (by me; I never served in Vigilant) Drugs violations while on a ‘live’ Trident submarine? Commodore Thompson might think so, but the rest of us can’t see that as a suitable defence of the country. “I wasn’t going to be buying his book, but I think it will be interesting to find out what he really thinks and whether he is typical.”

FOOTNOTE BY ME

There followed an interesting e-correspondence in this newspaper but not attacking me. This article triggered an argument over the Scottish Nationalist Party's defence policy between pro and anti nuclear deterrence factions. I had not realised that opinion was divided in the Nationalist camp.

Mail on Sunday and Mail Online

From transvestite parties to exploding cigars: Ex-nuclear submarine officer lays bare the startling truth about life aboard... and how a sudden disaster plunged them into DEEP trouble

- When steam began leaking, it was up to Senior Engineer Eric Thompson to stop it

- Dangerous scenario unfolded deep beneath the waves in a nuclear submarine

- HMS Revenge was carrying 16 Polaris nuclear missiles when trouble struck

By GUY WALTERS FOR THE MAIL ON SUNDAY

PUBLISHED: 22:01, 30 June 2018 | UPDATED: 12:20, 2 July 2018

When the steam suddenly leaked, the huge roar sounded like a jumbo jet taking off. It was hardly surprising, as the gas was rapidly discharging out of a massive, nuclear-powered steam generator, and quickly filling the compartment that housed the reactor. It was up to Senior Engineer Eric Thompson to stop the leak. If he could not do so, there was a chance that he and several other men would be killed.

Such a situation would be critical enough on dry land, but this was happening deep beneath the waves, in a 425ft submarine carrying 16 Polaris nuclear missiles, each eight times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. HMS Revenge, was part of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, and it was in an undisclosed location exactly 40 years ago this month when the potentially catastrophic accident took place. The vessel was part of Britain’s nuclear deterrent and it was in an undisclosed location exactly 40 years ago this month when the potentially catastrophic accident took place.

Thompson had an agonising decision to make – but he only had a few seconds. The best way to stop the leak would be to shut both main steam stops, which would halt the leak almost instantly. But that would come at a cost – a very big cost. If he did that, the nuclear reactor would be disabled and Revenge would be crippled, dead in the water.

‘We would have to surface and signal for a tug,’ Thompson recalls in a book he has just published about his service in this most secretive branch of the Royal Navy. 'Unthinkable. Revenge was a Polaris missile submarine on Strategic Nuclear Deterrent patrol. She was the country’s duty guardian. Surfacing and calling for a tug would mean breaching one of the country’s most highly guarded secrets – where we were.’ The stakes for Thompson could not have been higher. He was damned one way and possibly killed the other. But then he had an idea, a way that could perhaps save both lives and national prestige. It would be a gamble, but he had nothing to lose.

LAST month marked the 50th anniversary of the Royal Navy’s Submarine Service taking on the enormous burden of carrying Britain’s nuclear deterrent. On June 15, 1968, HMS Resolution slipped out of her dock at Faslane on the Clyde to start her first patrol. Resolution would be the first of four submarines in her class, and between them, from 1968 to 1996, they carried out an unbroken series of 229 Strategic Nuclear Deterrent patrols. For the entire duration, they were ready to fire their Polaris nuclear missiles at any target in the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc at just 15 minutes’ notice. It was an extraordinary achievement, and it required extraordinary men and machines.

Today, that duty is being carried out by the Navy’s four ageing Vanguard class submarines equipped with the Trident nuclear ballistic missile system, the fate of which is, of course, a political hot potato. Iain Ballantyne, author of The Deadly Trade: The Complete History Of Submarine Warfare From Archimedes To The Present, explains: ‘Paradoxically, the only way for Britain to have a voice in multilateral nuclear disarmament may be for it to build the new Dreadnought class submarines to give it the weight to demand an end to the nuclear balance of terror. ‘What is deeply worrying is the current situation where Theresa May’s Government – and preceding Labour, Tory and Coalition administrations – have so weakened the nation’s conventional deterrent forces that nuclear weapons become the first resort – rather than the last resort – if the nation is faced with an existential threat from a nuclear-armed foe, such as Russia.’

The role of the Polaris-equipped submarines is now being marked by a new, permanent exhibition at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum in Gosport, Hampshire. Called Silent And Secret, the exhibition reveals what life was really like for the submariners who spent months at a time in the deeps, unable to surface or to communicate with home. Their lives were in many ways bizarre. In the month before Resolution was deployed, the First Sea Lord, Sir Varyl Begg, informed the Defence Secretary, Denis Healey, that ‘service in SSBNs [ballistic missile submarines] in time of peace poses special morale problems which have no counterpart elsewhere or in the other Services’.

As recounted in the book The Silent Deep by Peter Hennessy and James Jinks, one of the biggest problems was the impact on family life. Because of the routine and frequency of the submariners’ lives – roughly three months on patrol, followed by three months back on shore – the men often complained that they could never be present for the births of their children. The response of one waggish officer was only partially understanding: ‘Sorry about that, but I promise I will have you there for the conception!’

The 143 men on board were not permitted to contact their families for the duration of the patrols but they were allowed to receive occasional ‘familygrams’ from loved ones. The only catch was that they could be only 40 words long. Their brevity made some humorous, for example: ‘Everything fine Painting Finished Vera coming next weekend Stockton ducks stolen Hampster [sic] eaten Helens sweater Our Love Joby.’ However, some familygrams brought worse tidings than pinched poultry or nibbled knitwear.

If there was some seriously bad news, it was withheld by the captain until the end of the patrol. Eric Thompson once had to inform a chief petty officer his wife had left him, and to another, he had to break the news that his father had died. But there was once worse. On the night before Repulse finished one of its patrols, Commander Bob Seaward had to summon one of his crew to inform him his wife and child had been killed in a car crash seven weeks before. ‘After more than ten weeks on patrol, that poor man would have been overjoyed at the prospect of a reunion with his wife and child the following day,’ Thompson observes, ‘only to be told they had been killed.’

In order to break the monotony of life on board, various entertainments were laid on. Of course, the Polaris subs operated well before Kindles and tablets, and today the entertainments seems almost quaint. Men played games such as Ludo and cribbage, or watched one of the 56 films brought on board. Quizzes were a staple activity and some aspiring disc jockeys even used the sub’s sound system to inflict their favourite music on crewmates. Fitness fanatics could use rowing and cycling machines, lift weights and even play table tennis. More cerebral types studied for public exams.

Even plays and revues were staged. The exhibition in Gosport shows that on one patrol, a group called the Polaris Players staged a show called A Deep Distraction, featuring morris dancing, a barber shop quartet, and even a group describing themselves as ‘Scottish opera’. Such theatrics provided an excuse for transvestism, and one snatched Polaroid shot shows a burly crew member in grotesque make-up, wearing lilac tights and a lurid green mesh top struggling to contain a false embonpoint the size of a couple of torpedoes. Eric Thompson recalls one such ‘lady’ being so attractive that pin-ups of him appeared all over the submarine. ‘It’s frightening what eight weeks without female company can do to a man’s judgment,’ Thompson reflects.

Such antics were not the only eccentricities that crew members displayed. One commanding officer was known to take a sports jacket and flannel trousers on every patrol and after the Sunday morning service, he would put them on and have a picnic in a private corner of the submarine. Banter and high jinks were also staple fare. Men could find themselves unable to get out of their bunks because they had been trapped inside by a wall of parcel tape. Cigars – yes, smoking was allowed – were sometimes fitted with exploding tips. Sleeping bags were placed into the rubbish compactor and returned to their owners as tight cubes.

Naturally, with so many confined in such a small space for weeks, personalities could clash and tempers could flare, but with training and officers keeping discipline, there is no account of things getting out of control. In the main, it appears the men looked out for each other, with many performing selfless tasks.

One of the most remarkable in the eyes of Eric Thompson was the supreme act of valour carried out by a crewmate called Tim Chittenden, who went scuba diving in the sewage tank to unlock the valve that released its contents overboard. With all the toilets blocked, had he not succeeded, the results would have been unthinkable. ‘He should have received an honour for that,’ Thompson writes.

Had Chittenden become ill as a result of his dive, he would have been treated by the submarine’s doctor, qualified to carry out many life-saving operations, as well as keeping his eye on the mental health of the crew. However, if a crewman was critically ill, he would have to survive until the end of the patrol. If he did not, his body would be stored in the food freezers. Nothing, not even life, was more important than maintaining the country’s nuclear deterrent.

Of course, it was that which united these men – their exceptional role as the Prime Minister’s trigger if he or she wanted to launch a nuclear strike against, in all likelihood, the Soviet Union. The submarine had to be ready at all times to fire its missiles and to keep the crew sharp, weapons systems readiness tests were carried out at random. When the orders for such tests came in, the crew had no way of knowing whether the test was the real thing, and it was not until the senior officers had decoded the full order that the crew would become aware they were not in fact consigning millions of people to their deaths.

It is chilling to reflect that each submarine had more firepower than all the ammunition expended in the Second World War. Of course, no such order has ever been issued for real. However, what was frighteningly real was the situation faced by Eric Thompson back in June 1978, with the critical leak of high-pressure steam.

With just seconds to spare, Thompson decided to take a gamble on what he later called an ‘obscure dockyard procedure never used at sea’. Too complex to explain here, Thompson’s gamble involved the equivalent of ‘emptying the domestic hot water tank straight into the toilet’. ‘For what seemed like an eternity, nothing happened,’ he recalled. The roaring of the steam continued. The humidity was unbearable. Then there was a mighty whoosh down the starboard steam range behind my back. 'It was like letting go the neck of an inflated balloon. The boiler had been deflated. The roar of steam had stopped.’

Although crisis had been averted, for the next eight weeks, the maximum speed was severely reduced and there would be no extra power to deal with any emergencies. Thankfully, none came. What Thompson soon discovered was that one of the crew had tried to squeeze through the jungle of pipework through the scalding steam to shut down the critical valve, but had been unable to make it. In doing so, he ripped his back open. Thompson recommended him for a medal and the crewman, James ‘Bungy’ McWilliams, was awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal.

Although there was no chance of a nuclear meltdown or the Polaris missiles detonating, it had been a close-run thing. It was the nearest – as far as we know – that our nuclear ballistic submarines have come to a major disaster. Meanwhile, the four Resolution class submarines are lying in a dock at Rosyth on the Firth of Forth, waiting to be decommissioned in a process costing many millions that will last until 2040. Once the secret killers of the deep, they can now be easily seen with Google Earth. It seems an ignominious ending for these awesome instruments of Armageddon.

- On Her Majesty’s Nuclear Service, by Eric Thompson, is published by Casemate Publishers, priced £19.99. Offer price £15.99 (20 per cent discount, including free p&p) until July 8. Order at co.uk/booksor call 0844 571 0640

- The Silent and Secret exhibition is now open at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum. Entrance is included as part of an 11-attraction annual pass for Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, which costs from £32 per adult. Book online at historicdockyard.co.uk

The Scotsman

(By Brian Wilson, former Labour Party Government minister and professional journalist, writing for The Scotsman, a major national daily. This article appeared as a full two-page spread in the Culture section along with four photographs and a front Page alert.)

It was June 1978, the Cold War was in full swing and the Polaris submarine, HMS Revenge, was on patrol somewhere so sensitive that 40 years later we still cannot be told.

A sudden roar that “sounded like a jumbo jet taking off” was followed by the cry of “Steam leak in the TG (turbo generator) room”. The scene was set for the most serious crisis in the history of Britain’s nuclear fleet – as far as we know. The detailed story of that event is told for the first time in a book by Eric Thompson, the Senior Engineer on watch aboard HMS Revenge that day. He went on to become Commodore in charge of the Faslane base and the submarines it served.

“I knew the emergency drill by heart”, he writes. ‘Shut Both Main Steam Stops’. That would shut off all steam to the engine room. At a stroke, it would kill the leak … it would also scram the reactor, the pumping heart of the submarine; the plant would automatically go into emergency cooling and there was no recovery from that at sea.“We would have lost our power source, be reduced to a dead ship. We would have to surface and signal for a tug. Unthinkable … We were in our top-secret patrol position. Our number one priority was to remain undetected”.

The undignified prospect of Britain’s nuclear deterrent limping back from wherever-in-the-world to Faslane on the end of a tug-line would, as Thompson points out, have had considerable political ramifications: “It would mean national humiliation. The credibility of our nuclear deterrent was at stake… Jim Callaghan’s government was riven by anti-nuclear sentiment… if the deterrent appeared to fail, Britain’s nuclear strategy would be holed below the waterline”.

In the end, crisis was averted by deploying an “obsure dockyard procedure never used at sea”. This involved by-passing the main engines so that the steam was fed directly into the condenser”. For the benefit of the lay audience, Thompson helpfully equates this to “emptying the domestic hot water tank straight into the toilet”. He writes: “For what seemed like an eternity, nothing happened. The roaring of the steam continued. The humidity was unbearable. Then there was a mighty whoosh down the starboard steam range behind my back… The boiler had been deflated. The roar of steam had stopped”.

Damage had been done and the vessel lost much of its power. “We could launch our missiles if necessary but our maximum speed was severely reduced… For the next eight weeks we would be walking a tightrope; one machine failure could bring everything tumbling down. “Submarines on deterrent patrol do not break radio silence. No one knew of our plight. Nobody would for another eight weeks”. One member of Thompson’s team was given a bravery award for his efforts to isolate the leak. “He had been within three metres of it before being driven back by the heat… he had ripped his back open whilst squeezing through a jungle of pipework”.

But let’s cut to the chase. While steam leaks and the derring-do required to address them are all very exciting, they also beg a bigger question. Was there at any point a threat of a nuclear accident? Eric Thompson remains adamant in his denial. “Absolutely not. The worst that could have happened was that we would have had to surface – and maybe I would have been poached alive”. You get the impression he might not have regarded this as a worse fate than being towed back to Faslane in the full glare of publicity and political outrage.

Thompson grew up in Coatbridge and his destiny was set when his father spotted an advert for scholarships to Britannia Royal Navy College, Dartmouth. In the face of intense competition, mainly from the public schools, he gained admission and embarked on a stellar Naval career which coincided with the hottest years of the Cold War. Another of that Dartmouth intake later became Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Boyce. The two became lifelong friends and Boyce provides a foreword in which he encapsulates an argument which goes to the heart of the debate about nuclear weapons. “The secrecy of the Submarine Service means that few outsiders know what life was like or what kept us busy. Yet we were performing the greatest public service of all, making a hugely significant contribution to the prevention of a third world war. In this, history shows that we succeeded: the Cold War ended peacefully”. Boyce continues: “It is no coincidence that in the first half of the twentieth century there were two horrific world wars but none in the second half; one could argue that the difference was that in the second half, we had a strategic nuclear deterrent”.

One could also argue, of course, against that proposition. What is unusual about this book is that it provides a perspective that often goes unrepresented – that of a professional practitioner who lived for decades in close proximity to nuclear weapons, while regarding them as instruments of peace rather than war.

In the aftermath of the crisis aboard HMS Revenge, Thompson recalls how he “staggered through the Reactor Compartment into the eerie tranquility of the Missile Compartment, as if I had entered another world in which 16 one and a half metre diameter vertical tubes each containing a Polaris intercontinental ballistic missile stood like silent sentinels…..The order of the day in the Missile Department was serenity”.

Eric Thompson, who now lives in Craigendoran, has spent much of his career in Scotland. He courteously sent me an advance extract from his book because of a nice reference, dating back to the early days of the West Highland Free Press and the decision to establish a torpedo testing range in the Sound of Raasay. His superiors thought that local opposition would be ill-informed and easily brushed aside. Thompson, whose father-in-law was from Lewis, knew better and probably enjoyed the spectacle as his superiors were taken apart at a public meeting in Kyle of Lochalsh, where the Commodore finally expostulated: “You should all count yourself damn lucky. If you were in the Soviet Union, you wouldn’t be allowed to ask these questions”! The range was established and complaints these days are only heard if there is to be a loss of civilian jobs. In the same way, the public assimilate most of what the military want and decide, on balance, that it is probably for the public good. Thompson’s down to earth memoirs and practical insights will probably help to reassure them.

At root, nuclear weapons involve a moral issue more than a political one. The case against is that it is wrong to possess weapons which cannot, under any conceivable circumstances, be used. The case in favour is Lord Boyce’s – that it is possession which guarantees that they will never be used. Take your pick.

Thompson says that he has written the book because, at 75, he is one of a diminishing band who saw the Cold War from his end of the periscope. As international tensions threaten to return to Cold War levels, he remains confident about the power of deterrence. “There will always be surrogate wars,” he says, “but ultimately, no regime is prepared to risk its own destruction”.

On Her Majesty’s Nuclear Service by Eric Thompson is published by Casemate at #19.99

Warships International Magazine

Nuclear Futures Magazine

Navy League of Australia

Subject: Review: On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service The NAVY Magazine of the Navy League of Australia Oct-Dec 2018 Issue

The author takes the reader on a journey – from when Britain gave back its Empire and attempted, through English-scholastic Globalism, to retain a position on the world stage. A stage upon which the Royal Navy had operated with near-continuous distinction for three hundred years. Fittingly and perhaps poignantly, the Author left the Royal Navy in 1998 just as the British Navy began its terminal decline.

Eric Thompson is an excellent story teller. He weaves anecdotes about his own misgivings, tragedies, and successes – including the death of his dear wife Kate to cancer – to conclude: I was from the luckiest generation ever to have walked this earth. I had served in the Royal Navy for thirty-seven years and never known war. I had lived my life in peace…For thirty-seven years I had never failed to do my duty…and death alone would part me from Kate – that too I had promised. In those words are the Author’s greatness; including fighting against the depravations of privatisation to retain HM Naval Base Clyde and winning the unions to his side against (what would become) a deeply divisive new-Labour Government. A rare achievement in the 1990s – as so much of what would befall the world in the 21st Century was inexorably put into play. The unsung and effective team-building undertaken by Eric as Commodore HMNB Clyde, contributed in some ways to the 2014 Scottish vote to stay in the UK. By that stage it was one of the few ‘industries’ Scotland had remaining.

Eric begins his journey through his remarkable Journal. Older readers will recall the Journal – a Naval diary, classified at times of war – that was fundamental to naval general training. As it had been in the days of Nelson. Sketches were required and the young aspirant was expected to record daily sea-going activities, and also critique and comment upon doctrine and the politics of the day. What is remarkable is the quality and gentleness of the mentoring by the Divisional Officers. One comes away with a wry smile, having been on the end of those pithy barbs – and learned to apply them oneself.

The Old Navy humour stands out; including narrating stories against himself showing others, including his female staffs, in a strong light. Eric was a champion of competent people – loved by them. He was ability conscious; gender and colour blind. Even the English liked him!

This is a rich book, telling the story of the Royal Navy across some of its great years as it fought to achieve a nuclear standing with and sometimes against U.S. intent. It is a book RAN leadership might do well to read – for it shows what may be done; and also how to avoid the pitfalls. A must buy for Christmas reading.